|

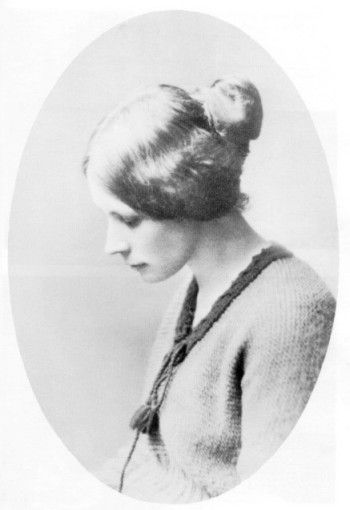

Flora Thompson.née Timms

(1876-1947)

|

| Flora Thompson. 1876-1947 |

The eldest daughter of Albert and Emma Timms,Flora

Jane Thompson was born in the tiny Oxfordshire hamlet of Juniper Hill, near Brackley, on 5th December 1876. She attended

school in the neighbouring village of Cottisford. After leaving school at fourteen, and moving away from home, for the first

time, she worked as a post-office clerk at the Fringford post-office. After four years she left Fringford, and took a number

of short holiday-relief engagements in various rural post-offices, then applied for and got the job of assistant at the Grayshott

post-office, in Hampshire. There, in due course, she met her future husband John Thompson,himself a post-office-clerk who

later became a postmaster. In 1903 John Thompson was transferred to the main post-office in Bournemouth, he and Flora were

married and began life together in this large sea-side town. Flora was then twenty-six.

The Thompsons remained in Bournemouth

for thirteen years, during which time their two elder children, Winifred and Basil, were born. In 1916 they moved to Liphook

in Hampshire, and a younger son, Peter was born a year later. They lived in Liphook for twelve years, until another, and final

posting for John Thompson took them, in 1928, to Dartmouth, where they remained until his retirement in 1940. In the early

years she supplemented their meagre income with journalism, writing nature essays for The Catholic Fireside, the Daily News,

The Lady, and other papers, and in 1921 she published a volume of verse, Bog-myrtle and peat. She is remembered for her autobiographical

trilogy Lark Rise to Candleford (1945), published originally as Lark Rise (1939), Over to Candleford (1941), and Candleford

Green (1943), works which evoke through the childhood memories and youth of third-person 'Laura' a vanished world of agricultural

customs and rural culture. There is a selection of works by Margaret Lane, A Country Calendar and other writings (1979), with

a biographical introduction.

Flora Thompson died on 21 May 1947, and was buried in Dartmouth.

The Oxford Companion to English Literature.

© Margaret Drabble and Oxford University Press. 1995.

Lark Rise

1

Poor People's Houses

THE

hamlet stood on a gentle rise in the flat, wheat-growing north-east corner of Oxfordshire. We will call it Lark Rise because

of the great number of skylarks which made the surrounding fields their springboard and nested on the bare earth between the

rows of green corn

All around, from every quarter, the stiff, clayey soil of the arable fields crept up; bare, brown and

windswept for eight months out of every twelve. Spring brought a flush of green wheat and there were violets under the hedges,

and pussy-willows out beside the brook at the bottom of the 'Hundred Acres' ; but only for a few weeks in later summer had

the landscape real beauty. Then the ripened cornfields rippled up to the doorsteps of the cottages and the hamlet became an

island in a sea of dark gold.

To a child it seemed that it must always have been so; but ploughing and sowing and reaping

were recent innovations. Old men could remember when the Rise, covered with juniper bushes, stood in the midst of a furzy

heath - common land, which had come under the plough after the passing of the Inclosures Acts. Some of the ancients still

occupied cottages on land which had been ceded to their fathers as 'squatters' rights', and probably all the small plots upon

which the houses stood had originally been so ceded. In the eighteen-eighties the hamlet consisted of about thirty cottages

and an inn, not built in rows, but dotted down anywhere within a more or less circular group. A deeply rutted cart track surrounded

the whole, and separate houses or groups of houses were connected by a network of pathways. Going from one part of the hamlet

to another was called 'going round the Rise' , and the plural of 'house' was not 'houses' , but 'housen' . The only shop was

a general one kept in the back kitchen of the inn. The church and school were in the mother village, a mile and a half away.

A road flattened the circle at one point. It had been cut when the heath was enclosed, for the convenience in fieldwork

and to connect the main Oxford roaed with the mother village and a series of villages beyond. From the hamlet it led on the

one hand to church and school, and on the other to the main road, or the turnpike, as it was still called, and so to the market

town where the Saturday shopping was done.. It brought little traffic past the hamlet. An occasional farm wagon, piled with

sacks or square-cut bundles of hay; a farmer on horseback or in his gig ; the baker's little old white-tiled van; a string

of blanketed hunters with grooms, exercising in the early morning; and only one of the old penny-farthing high bicycles at

rare intervals. People still rushed to their cottage doors to see one of the latter come past.

A few of the houses had

thatched roofs, whitewashed outer walls and diamond-paned windows, but the majority were just stone or brick boxes with blue-slated

roofs. The older houses were relics of pre-enclosure days and were still occupied by descendants of the original squatters,

themselves at that time elderly people. One old couple owned a donkey and cart, which they used to carry their vegetables,

eggs, and honey to the market town and sometimes hired out ar sixpence a day to their neighbours. One house was occupied by

a retired farm ballif, who was reported to have 'well feathered his own nest' during his years of stewardship. Another aged

man owned and worked upon an acre of land. These, the innkeeper, and one other man, a stonemason who walked the three miles

to and from his work in the town every day, were the only ones not employed as agricultural labourers.

|

|

|